45. Democracy Can Move Backward. Citizens Can Pull It Forward.

What “civic muscle” looks like when the state forgets its job description.

🎧For the parts that felt too raw to fit into paragraphs: here is the companion audio for today’s post.

The Week I Learned That Being Seen Can Be Safe

Last week, I sent a newsletter that felt unusually personal.

To be honest, revealing myself so clearly felt daunting.

There is a lingering fear: What if I share a piece of my soul and am misunderstood? What if I make myself too visible?

But your response was overwhelming. I received more messages and warm support than ever before. Thank you, truly, for holding space for my words.

Because of that support, I feel empowered to share another piece of what I am witnessing today.

What “Gwangju” Means to Koreans

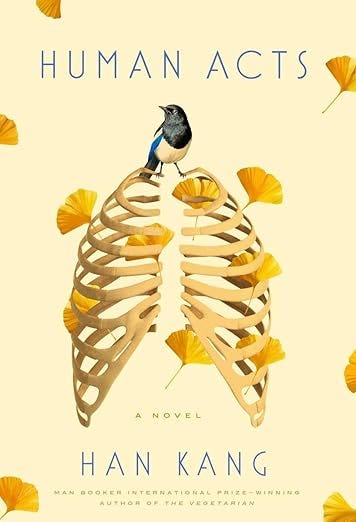

With Han Kang’s 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature, many global readers encountered Human Acts (소년이 온다), her novel about the 1980 Gwangju Uprising, for the first time. It is not simply a book “about a protest.” It is about what happens when the state decides certain bodies can be crushed for the sake of order, and then insists those bodies had it coming.

For Koreans, “Gwangju” is not shorthand for dissent. It is shorthand for targeted state violence and the propaganda that follows.

From May 18 to May 27, 1980, Gwangju became the epicenter of a pro-democracy uprising against South Korea’s military government. Elite paratroopers were sent in. Their brutality drew more citizens into the streets. Official tallies long hovered between roughly 165 and 200 dead, while many in the city insisted the true number was far higher. Scholars today cite a wide range, from the hundreds to well over a thousand.

Then came the part Koreans still say with a tightening of the throat. In the predawn hours of May 27, tanks and armored personnel carriers moved in. The uprising was crushed in hours.

When Power Picks a City

Recently, many Koreans watching the United States have said what is happening in Minnesota feels like Gwangju. Not because the details match perfectly, but because the logic is familiar.

Why do governments choose certain places for their hardest displays of force?

Gwangju was targeted for many reasons, including political geography. It was the provincial capital of South Jeolla (전라남도), a region long associated with opposition politics and the resentments that come from being treated as peripheral. In other words, it was legible to power as the “wrong kind of place.”

But there is another reason, and it matters now.

A city can be chosen not only to be controlled, but to be used. Not only to arrest, but to instruct.

A city becomes a lesson.

Once a city becomes a lesson, the struggle is no longer only over policy. It is over narrative. Who gets labeled “dangerous.” What gets defined as “order.” Which bodies are treated as expendable so everyone else learns to stay calm.

A Job Description for a Decent State

Here is where a Korean public intellectual offers a yardstick I keep returning to.

In earlier issues of this newsletter, I reviewed two books by Yu Si-min, a former politician and one of South Korea’s best-known civic writers. In What Is a State? (국가란 무엇인가), Yu offers a blunt definition of what a decent state is supposed to do: establish justice among people, protect citizens from danger, and act without bias.

It is not poetry. It is a job description.

And it is precisely what collapses when the state begins to treat certain groups as disposable, and certain places as examples.

Yu also wrote something else that has been haunting me. In My History of Contemporary Korea (나의 한국 현대사), he argues that if you look at South Korea “in itself,” you can easily list a thousand failures: inequality, precarity, unfinished justice. But if you compare the present to the past, you see transformation. Korea is “better in almost every way,” not because it is pure, but because it moved from “ugly and irrational” toward “more beautiful and reasonable.” It is a country he can feel “limited pride” in, without closing his eyes to its shame. He argues that progress is measured by the distance traveled from darkness.

That comparison has been difficult for me to make about the United States.

Twenty-Three Years in America, and the Question I Cannot Shake

I came to the United States 23 years ago, and somewhere along the way I became American.

Back then, America felt sturdy. Institutions held. Norms mattered. Power had limits. When Americans spoke about democracy, there was an assumption beneath the words: of course we move forward.

Now I am not so sure. If I compare America today with the America I first met, I cannot honestly say we feel more protected from political violence, more confident that the law restrains the powerful, or more certain that citizenship is not narrowing in real time.

And I want to be careful here. I’m not saying nothing is good. I’m not romanticizing the past. The past had its own brutalities, and many people never experienced America as “sturdy.”

What I’m saying is this: I feel the ground shifting under the word “citizenship.” And I’m trying to understand what that shift does to everyday life, to families, to communities, to children listening to the news.

That is precisely why this moment may be, perversely, an opportunity.

A Message From Koreans Who Have Been Here Before

Here is the message from a country that lived through Park Chung-hee’s developmental dictatorship and survived Chun Doo-hwan’s military rule, a country that still carries the wound of Gwangju and has learned, the exhausting way, that history does not stop after one victory.

I was born in 1980, the year Gwangju happened. Park Chung-hee was gone by then, but his rule shaped the air my parents breathed. Chun Doo-hwan’s regime shaped the rules of fear, the rules of silence, the rules of what you were not supposed to say out loud. Even if my own memories begin later, the country’s memory does not.

And here is the part outsiders often miss. From far away, Korea’s story can look like a clean arc: dictatorship, uprising, democratization, then accountability.

Up close, it felt nothing like a straight line.

Koreans learned democracy the way you learn endurance: by realizing you do not “arrive” and get to rest. You win something, and then you are tested again.

That is why I recognize something in the despair many Americans felt when Trump became president again. Koreans know that particular kind of disbelief.

Koreans learned that disbelief early. After Chun Doo-hwan, we fought our way to the 1987 election, and the first president of the “new” era was Roh Tae-woo, Chun’s closest ally, another general from the same military circle. It felt like history was mocking the people who had just risked everything. Chun and Roh were not identical, but they belonged to the same structure, shaped by the same coup-era networks and the same assumption that the state could be managed by a small inner ring.

We felt it again in 2007, when Lee Myung-bak, the "CEO president," was elected. Many of us stared at the news in disbelief, asking: "Really? Him? After everything we went through to restrain corporate and authoritarian power?"

We felt it again in 2012, when Park Geun-hye, the daughter of the dictator Park Chung-hee, rose to the presidency. It felt like history playing a cruel joke, as if the country was being pulled backward by its own shadow.

And we felt it most recently in 2022, when Yoon Suk-yeol took office. For many, that was a moment where despair turned physical. We had already paid so much to build a democracy that could withstand such tests, yet the sickening thought returned: Was all that struggle only a temporary interruption?

But the Korean answer, hard-earned through decades of practice, is no. These presidencies did not remain untouchable. Lee (2007) was eventually convicted and imprisoned. Park (2012) was impeached, removed, and imprisoned. And Yoon (2022), too, was impeached and removed before his term ended.

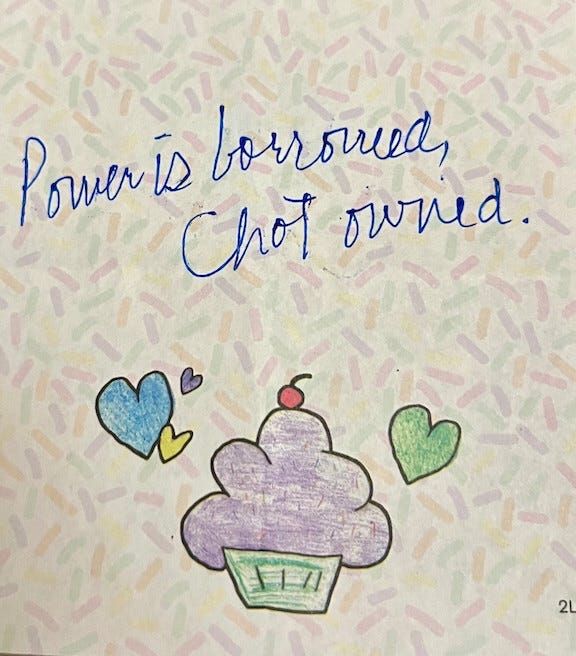

The struggle was the point. The struggle built the muscle. Accountability is not a single dramatic act; it is the result of habits ordinary people build together over years: protest culture, legal culture, and a shared expectation that power is borrowed, not owned.

What This Is Not About

What matters to me is not the thrill of watching powerful people fall.

It is what had to exist for that to be possible in the first place.

Accountability is not a single dramatic act. It is the result of habits ordinary people build together over years. Protest culture. Legal culture. A shared expectation that power is borrowed, not owned. A refusal to treat impeachment, resignation, or prosecution as unthinkable.

That is the real inheritance of Gwangju. Not a myth of purity, but a method.

The Part Americans Often Underestimate

Korea’s lesson is not that “Koreans are better at democracy.”

Korea is not a fairy tale.

Korea is not a moral exception.

Korea is messy and often exhausting. It disappoints its own people, repeatedly.

But Korea has learned something that matters, and it was learned the hard way. Accountability is not a mood. It is not a viral moment or a burst of righteous anger. It is habits. It is culture.

It is the slow, collective building of an expectation that power is borrowed, not owned. And once that expectation settles deep enough, even presidents stop being untouchable.

In other words, democracy is a set of muscles, and muscles only grow through repetition.

People build those muscles in public, together, often in ways that look ordinary up close: phone calls, union meetings, court filings, neighborhood groups, showing up at city council, donating twenty dollars to a legal defense fund, voting like it is not only a right but a responsibility to future strangers.

This is also why evidence alone is not enough. We live in a world where almost everything can be recorded. The problem is that evidence does not automatically become consequence. A video can go viral and still evaporate into nothing. A headline can shock you and still become background noise a week later.

What turns witnessing into consequence is civic follow-through: institutions that can be pressured, courts that can be engaged, local officials who can be called, and community groups that can absorb fear and turn it into action.

A Community That Won’t Normalize Coercion

If Minnesota feels like a lesson right now, it is not because Minnesotans are sitting still while power lectures them. It is because Minnesotans are actively refusing the lesson that coercion is normal.

You can see that refusal in the way local leaders, neighborhood groups, faith communities, and ordinary residents have pushed back, not only with outrage but with organization. They have demanded accountability for deaths tied to federal immigration enforcement, pressed for investigations, and insisted that “public safety” cannot mean lawlessness. They have also built practical systems of care: legal hotlines, mutual aid, rapid response networks, and public guidance for neighbors who are frightened but do not want to disappear.

That is where the comparison to Gwangju stops being metaphor and becomes a question of practice. In moments like this, the decisive question is not whether a city is targeted. It is whether the people of that city allow fear to redraw the boundaries of belonging.

Minnesota, so far, is showing something worth naming: a community can be pressured in public and still refuse to surrender its civic standards.

The Ending Korea Keeps Relearning

Koreans are familiar with the moment when you think, “We fought so hard. How is this happening again?”

We are also familiar with what comes next, if citizens choose it.

You keep going anyway.

You keep showing up, not because you are optimistic, but because you have decided the state does not get to forget its job description. You keep widening the circle of who counts. You keep insisting that no group is disposable. You keep doing the unglamorous democratic work that makes dramatic moments possible later.

Democracy can move backward. Citizens can pull it forward.

That is not a slogan. It is a description of reality.

As another Korean, this great American city reminded me of Gwangju a lot. I just hope that maybe some American scholars and politicians learn actively from our history and make a note of what had to be done, what was the difference that prevents things from getting better. Or normal at least. Thank you again.