40(20). What is the State? The Philosophy Behind Korea's Democracy

Why Koreans Keep Returning to the Candlelit Square

Hello, readers!

We’ve just finished a four-part journey through Yu Si-min’s My History of Contemporary Korea, from the ruins of war to the “miracle on the Han River,” from military dictatorship to candlelight protests.

You’ve seen what happened:

Part 1: From the postwar ruins, two clashing desires emerged: survival and dignity

Part 3: Park Jong-cheol and Lee Han-yeol, whose deaths forced a whole generation to say “Enough”

But there’s one question we haven’t fully answered.

Why does this keep happening?

Why did Koreans flood the streets again in December 2024, calling for President Yoon Suk Yeol’s impeachment, not with violence, but with light sticks and careful legal arguments?

Why did the crisis move through institutions so insistently, from protest to parliamentary impeachment (December 14, 2024) to a Constitutional Court ruling that removed Yoon from office (April 4, 2025)?

Why do Koreans keep acting like democracy isn’t something you win once and keep forever, but something you have to defend, again and again?

The answer, or at least one of the best Korean answers I know, lives in a book most Koreans recognize by name, even if they have not read it cover to cover.

And today, I’m giving you the key parts.

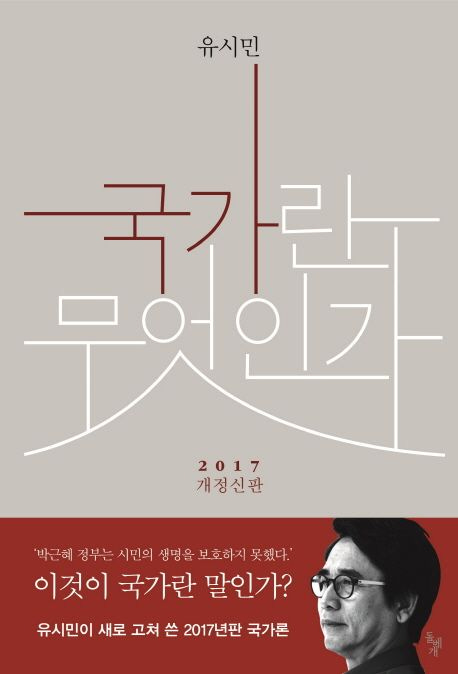

Bonus K-Book: What Is the State? (국가란 무엇인가) by Yu Si-min

Yu Si-min’s What Is the State? is not a “Korea book” in the narrow sense. It is a citizen’s toolkit. It asks a blunt set of questions that can travel across borders:

What is the state? Who should rule it? What should its moral ideal be? How do we get closer to that ideal? And what should ordinary citizens and politicians actually do?

If that sounds abstract, Yu’s point is the opposite. This is the question hiding under every concrete fight you have watched in this series.

Why this book matters for anyone who cares about democracy

Yu’s starting point is simple and brutal: without a decent state, it is nearly impossible for most people to live a decent life.

That sentence refuses two comforting fantasies at once.

One fantasy says: if we just elect good people, the machine becomes moral.

Another says: the state is automatically the villain, so the goal is simply to shrink it and walk away.

Yu doesn’t buy either. He argues the real question is not “more state” or “less state.” It is whether the state does three basic things well:

sets up justice between people

protects citizens from different kinds of risk

refuses to lean only toward the powerful

The state is not the government

One of Yu’s most quietly radical moves is a distinction many democracies forget in daily life:

Governments come and go. The state remains.

When we blame everything on “the government,” we often miss the deeper problem. Sometimes the real issue is not the people currently in office. It is the shape of the state itself, the incentives it creates, and what it considers “normal” when nobody is watching.

That is why crises repeat. New actors enter, but the stage stays the same.

Six goals that sound obvious, until you try to hold them together

Yu points to constitutional ideals as a kind of job description for the state. He treats the state’s highest goals as a set, not a menu:

freedom, welfare, equality, safety, peace, and environment.

Most political arguments happen because we quietly pick one value as the “real” one, then use it to crush the others.

Security can crush freedom.

Freedom can crush equality.

Growth can crush the environment.

Safety can become a pretext for surveillance.

Peace can become an excuse to ignore injustice.

Yu insists a decent democracy has to do the harder thing. It has to hold these values together, in tension, without turning one into a god.

The social contract, in plain language

To explain why states exist at all, Yu leans on Hobbes and the “state of nature” thought experiment.

Imagine a world without shared law. No common standard of right and wrong. Life collapses into fear, vulnerability, and preemptive violence.

Hobbes’s solution is terrifying and practical: people create a shared power that everyone fears and obeys. That power becomes the state, the institution that holds a monopoly on legitimate violence.

Yu is clear about the “contract” part.

Nobody actually signed it.

It is a model, a myth that helps us see why people tolerate concentrated power in exchange for protection. Then Yu shows how different theories of the state choose different “highest priorities,” and how those priorities can become excuses.

Patriotism, and the beast behind it

This is the chapter that lingers.

Yu begins with a question that sounds innocent until it isn’t:

What do we mean when we say we love our country?

The state itself? The people? The values? The shared fate?

Then he points to the uncomfortable fact that separates the state from every other community you belong to:

The state is the only institution that can lawfully imprison, kill, and wage war in our name.

No fan club can do that. No church can do that. No alumni association can do that.

Only the state can.

And patriotism is the emotion that makes many of us accept it.

Yu argues there is often a beast hiding behind noble patriotism: hostility toward outsiders, contempt toward other nations, and the readiness to turn sacrifice into a civic requirement. He brings in Tolstoy as the extreme mirror, the writer who saw patriotism itself as evil.

You do not have to agree with Tolstoy to feel Yu’s warning. It is genuinely hard to draw a clean line between “good patriotism” and the kind that prepares people for hatred and war.

This hits differently if you think about conscription, national security laws, and the way both Koreas have long spoken the language of sacrifice.

Before we go behind the paywall:

In the paid section below, I’ll walk through Yu Si-min’s idea of a “good state” (미덕국가), why he thinks progressive politics is basically “making the state do good,” and how this framework explains Korea’s path from security-first rule to today’s welfare demands. I’ll also share a simple thinking guide you can use on your own country’s headlines.

If you’re a paid subscriber, thank you. Your support is what makes this kind of slow reading, translation, and bridge-building possible.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Understanding Korea, One Story at a Time to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.