46. No Ice, Please: A Korean Mom’s Guide to Warmth

What temperature means in Korean care—and why it follows us everywhere.

Want the audio companion to this essay? Listen to the companion podcast here. It adds a few extra stories and context that didn’t fit on the page.

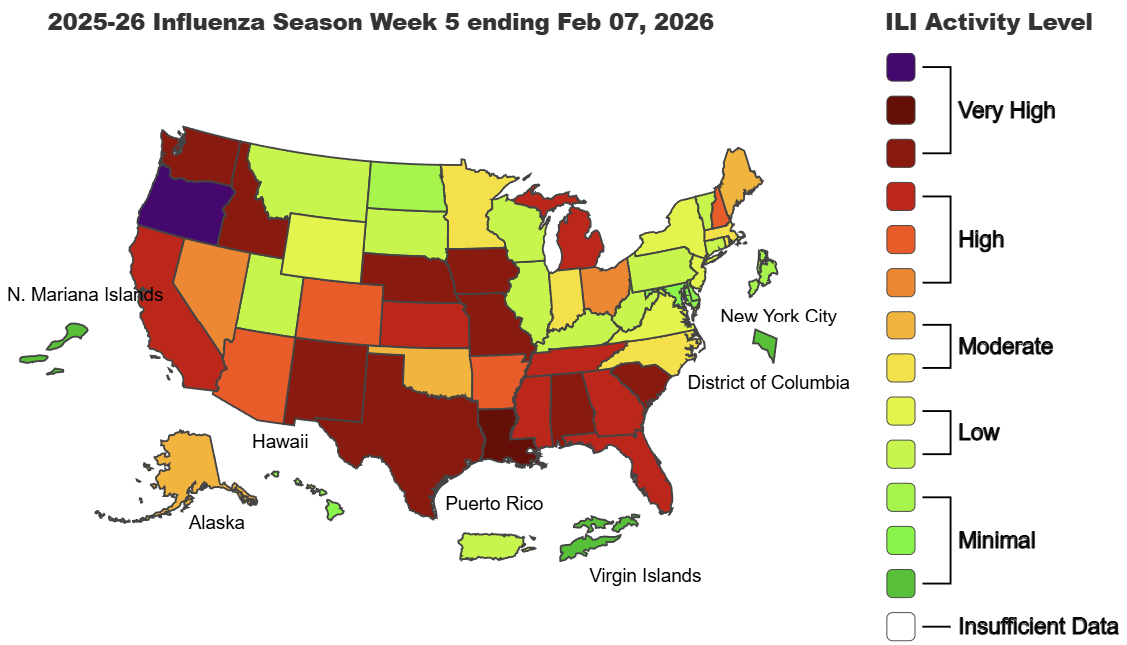

“Seasonal influenza activity remains elevated nationally,” the CDC wrote in its latest FluView update. Compared with late January and early February, some states have improved, but Washington State has gotten worse. And that map isn’t just a flu map. It’s something you can feel in my house.

About a month and a half ago, I published my first post of the year and mentioned that my daughter had been sick. I didn’t realize I was also launching a recurring series titled The Child Gets Sick Again.

This time, it hit fast: high fever, vomiting, headache. The kind of symptoms that make you grab your keys with one hand and your phone with the other, already rehearsing the urgent-care check-in speech in your head.

We went in for a flu test because last time we went too late for Tamiflu, which works best when started within the first 48 hours of symptoms, and I was still irrationally mad about it, like I’d missed a train. The neighbor’s kid started Tamiflu on time and bounced back quickly; my daughter, without Tamiflu, took nearly two weeks for her symptoms to fully disappear.

When the flu test came back negative, the doctor looked genuinely puzzled. She told me my daughter was her fourth patient that day who presented exactly like the flu but tested negative. When I messaged the teacher to explain the absence, the reply came back with the weary solidarity of someone inside the same storm: lots of kids were out, and the teacher herself had been sick, too.

Thankfully, compared to the long, grinding illness of last month, she recovered quickly. By day four, she was “energetic” again. But as I watched her bounce back, I noticed something about myself that feels deeply Korean.

Outside of the three to four glorious months when the Pacific Northwest turns into a postcard, the sentence I say most to my daughter is:

“Dress warmly (옷 따뜻하게 입어).”

Why does Korean care begin with temperature?

Two Languages, One Body

What’s happening here isn’t really a disagreement about medical facts. It’s a collision between two frameworks for understanding what a body is and how it gets better.

In the American medical system, temperature is:

a number you measure

a symptom you manage

a variable you control with a fever reducer

It’s mechanical. Observable. Documentable.

In the Korean framework I inherited, temperature is something else entirely:

a state of balance

a measure of vulnerability

a clue about whether your “inside” is holding steady

The language gives it away. Koreans don’t just talk about being “cold.”

We talk about cold energy (찬기, chan-gi), which is less “brr, it’s chilly” and more “something got in.”

We don’t just say “I’m tired.”

We say “We have no vital energy (기운이 없다, gi-un-i eopda).”

Gi-un (기운) is not a mood. It’s closer to life force, the animating current that makes you feel like yourself.

So when a Korean mother says, “Your stomach needs to stay warm,” she’s not talking about surface temperature. She’s talking about the integrity of your core.

Warmth isn’t just comfort. It’s defense.

When the Doctor Says “Fine,” But the Caregiver Hears “Fragile”

In the U.S., when your child is sick, you learn the language of metrics.

What’s the temperature, numerically? How many ounces of fluid? How many hours since the last dose? Are symptoms improving or worsening?

It’s not “cold.” It’s not “hot.” It’s 101. It’s 102. It’s documented.

Korean care has its own language, and you can hear it in a familiar scene, especially if you grew up in a Korean household, married into one, or have ever spent time around Korean mothers and grandmothers:

Don’t stand in the cold wind.

Don’t drink cold water.

Put on socks.

Eat something warm.

A pediatrician may say, “She’s fine.”

A Korean mother or grandmother will say, “She’s recovering.”

In other words, the diagnosis is over, but care is not.

There’s an entire worldview packed into one classic sentence:

“Don’t catch a chill (찬바람 쐬지 마).”

It’s an instruction, yes. But it’s also a philosophy. It assumes illness isn’t a switch that flips off when the fever breaks. It’s a process. A passage. And the body, especially a child’s body, is a place you guard.

The Moment Care Turns into Climate Control

Here is what “Korean care” looks like in my very American house:

We have multiple hot packs. The kind you wrap around your belly. The kind you drape over your shoulders like a small heated pet.

We have two heated blankets, because one heated blanket is like one chopstick: technically functional, emotionally incomplete.

And in my childhood home in Korea, the electric mat wasn’t a luxury. It was a household fact, like rice.

I’ve also noticed something about myself that is both funny and revealing. When we go to a restaurant with my daughter, I always say, “No ice for her water, please.”

I do this automatically, like a reflex. I live in America, where ice water arrives with the confidence of a national ideology. It shows up uninvited. It’s free. It’s abundant. It’s proud of itself.

And yet, there I am, a Korean mom, politely negotiating peace terms with a cup.

It’s not that I think ice will ruin her life.

It’s that cold feels… wrong.

Not medically wrong. Culturally wrong. Like wearing shoes on a bed.

Cold Treats, Warm Beliefs

This is where the two care cultures collide in the funniest way.

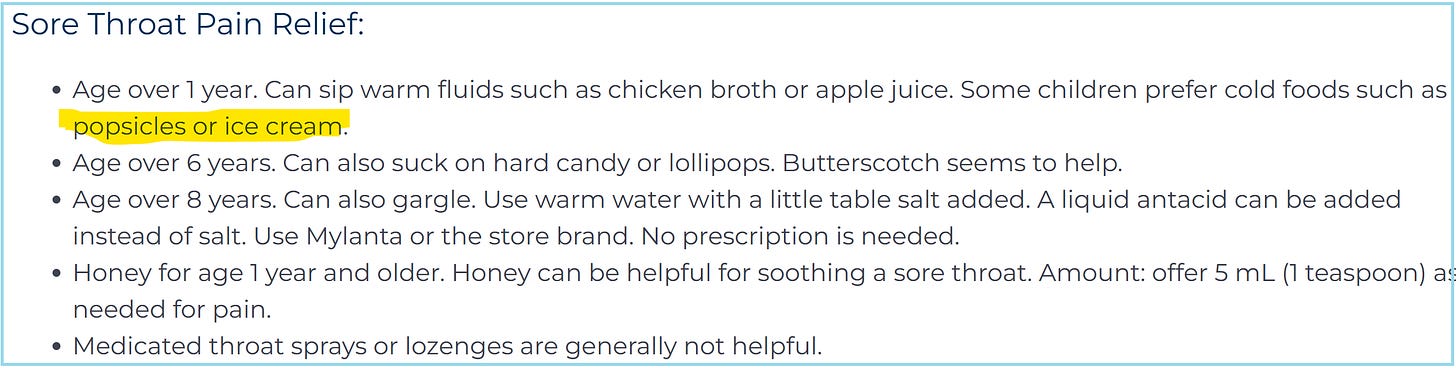

In American pediatric home-care guidance, cold foods can be a perfectly reasonable comfort measure for sore throats. Seattle Children’s Hospital, for example, notes that some kids prefer cold options like popsicles or ice cream, even while warm fluids help others.

My daughter has absolutely internalized this information. A doctor once told her popsicles could help, and she later asked me, with the confidence of someone citing case law, why I wasn’t providing the prescribed treatment.

She was not wrong.

I simply refused to comply.

An American parent hears “popsicles” and thinks: great. Easy calories. Hydration. Everyone wins.

A Korean grandmother hears “popsicles” and thinks: are you trying to raise this child inside a refrigerator?

I’m exaggerating. Slightly. But only slightly.

Because Korean care is not only about soothing symptoms. It’s about protecting gi-un (기운). Guarding the body’s equilibrium. Keeping your inside from collapsing.

That’s why Koreans say things like:

“기운이 없어.” (Gi-un-i eopseo.) — “I have no energy.”

“속이 차.” (Sok-i cha.) — “My insides feel cold.”

“찬기운이 들었어.” (Chan-gi-un-i deureosseo.) — “Cold energy got into me.”

These aren’t just metaphors. They’re a folk physiology, a lived grammar for describing what it feels like to be depleted, vulnerable, off-balance.

In that grammar, “cold” is not merely a temperature. It’s a force. A disruptor. A thief.

And “warmth” is not just comfort.

Warmth is protection.

Warmth is restoration.

Warmth is the house doing medicine.

Warmth as a Relationship, Not a Number

I think this is the difference that makes Korean care feel simultaneously tender and, to outsiders, a little intense.

In the American model, temperature is a number you monitor.

In the Korean model, temperature is something you offer.

You don’t just take the child’s temperature. You make the environment warm. You wrap the body. You boil water. You build a small climate of safety around someone who is fragile.

Warmth is care you can see.

It is labor that leaves evidence.

A blanket tucked tighter.

A bowl of warm porridge.

Socks that appear on your feet as if summoned by ancestral instinct.

This is why, even after the fever is down, the Korean caregiver keeps going. Because in that worldview, recovery is not merely the absence of symptoms. It’s the return of equilibrium.

And equilibrium is something you help create.

A Small Confession: The Undershirt (That No One Else Wears)

My daughter recently informed me that none of her friends wears an undershirt. (For context: most of her close friends have no connection to Korea whatsoever.)

In Korean households, that undershirt—nae-bok (내복) or me-ri-ya-seu (메리야스)—is not just a garment. It’s a preventative strategy. It’s the thing your mother makes you wear under your clothes because, for reasons you don’t yet understand, the belly must be protected.

I usually see my mom in Korea about once a year. And every time, without fail, she buys my daughter a stack of undershirts. As if this is simply what grandmothers do. As if my child’s torso is a national heritage site.

When my daughter changes clothes around other kids at the pool, it’s almost comical. She is often the only child in an undershirt.

(Including in summer. Yes. Including in summer.)

So I asked my Korean friends who have kids.

Every single one—whether they have sons or daughters—said the same thing: “Of course you make them wear it. Why wouldn’t you?”

And when I was growing up, I heard a version of the same sentence so many times it might as well have been printed on my birth certificate:

“Your belly should always be warm.”

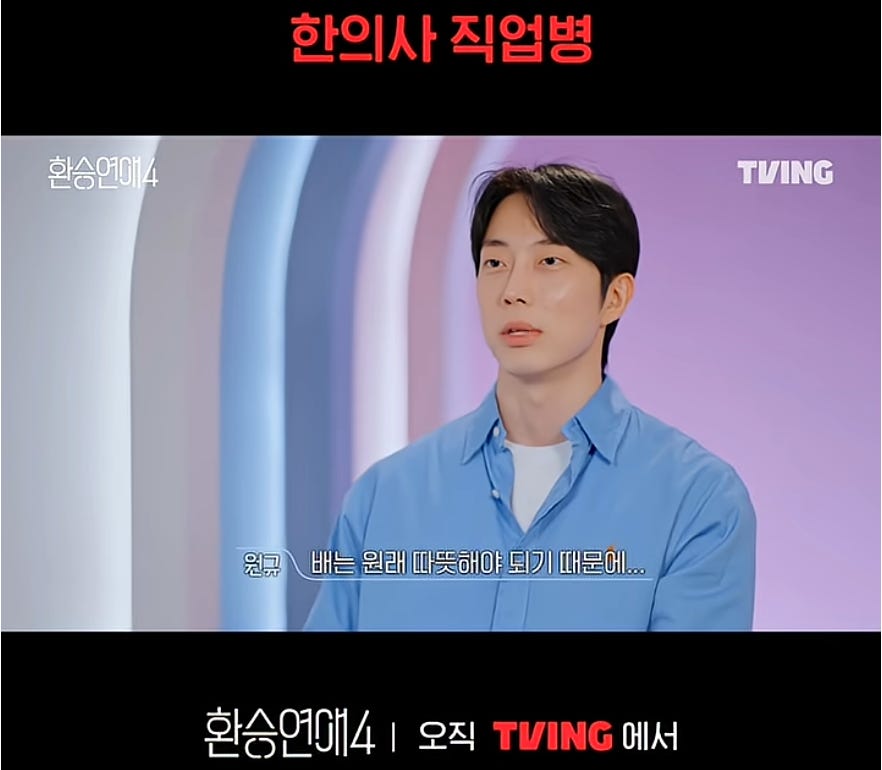

A quick detour into Korean pop culture, because this is too perfect not to share.

In the Korean dating reality show Hwanseung Yeonae (환승연애), also known in English as EXchange, one of the cast members is a Korean medicine doctor, a hanuisa (한의사). On a date, a woman shows up in a crop top. And the very first thing he says, on camera, in front of everyone, is: “Your belly shouldn’t be cold.”

The producers laugh. The cast loses it. Even the woman looks at him like, Are you serious?

He is serious. Because in his worldview, a cold belly is not just uncomfortable. It is a risk. And he cannot switch that instinct off, not even on a date.

Warmth Is a Worldview

Warmth, in Korean care, is not just a remedy.

It is a worldview.

It is a way of saying: recovery deserves a protected space.

It is the house performing care.

Next Week: Where Warmth Became Architecture

Next week, I’ll zoom out from the body to the house: why warmth in Korea isn’t just something you wear, but something you live on—and how that shaped a whole culture of care. I’ll also dig into the deeper “why” behind the obsession: the history, the climate, and the medical logic that taught Koreans to treat warmth as protection.

(And a quick note: my monthly review of Korean-language books will be published in the first week of March. Thank you for your patience and flexibility.)

Until then, may your tea be warm, your blankets be plentiful, and your child’s fever be brief.

This was a wonderful post! And it brought so many things I’ve noticed (about Koreans as depicted on screen) in contrast to my American life. I really appreciated it. 감사합니다

This is so true!! And I've been to traditional medicine Korean doctors and they also told me not to drink cold things, no ice, to cover my neck, not to use A/C...things that honestly love! But I believe they are right, anyway.