Bonus Audio: Prefer listening? I created a podcast version using NotebookLM, with extra insights and stories that didn’t make the post. Just hit play!

This is Part 9 of the series The People’s Mandate: Korea’s Democratic Edge, a special miniseries within Growing Up in Korea (Part 19).

Over the last two weeks, we zoomed out to ask why Korean stories hit us right in the feelings—and explored how that emotional force has been channeled into powerful works set against the backdrop of Japanese colonial rule.

This week, we zoom way in—to a single prop hiding in plain sight on Netflix’s KPop Demon Hunters.

If it looks familiar, it might be because it’s also the inspiration behind my Substack logo!

Ready to crack the code?

The Screen You’ve Seen—but Never Clocked

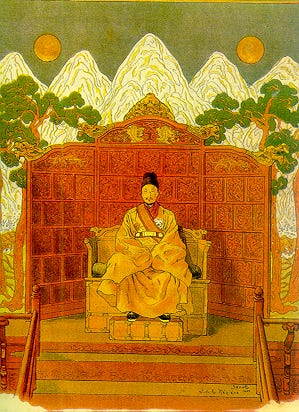

Whenever HUNTR/X unleashes its chart-topping hits, a folding screen glows behind them: a red sun, a pale moon, five dark peaks, waterfalls, pines, and waves. That’s Ilwol Obongdo (일월오봉도, “Sun–Moon–Five Peaks”).

Five centuries ago, it sat behind every Joseon-dynasty throne, broadcasting, in brushstrokes, “the king is in the house.”

A Cosmic Control Panel in Seven Brushstrokes

At first glance, it looks like just a pretty painting: two celestial orbs, five oddly shaped mountains, a few trees, and some water.

But every stroke in the Ilwol Obongdo (일월오봉도) is intentional—coded with meaning, layered with philosophy, and embedded with centuries of worldview. Think of it as a cosmic control panel for how the world should function—nature, kingship, and the flow of time, all in balance.

Here’s what’s actually going on:

☀️ Sun (IL, 일)

The red sun represents yang—the active, masculine force tied to daylight and the king. It symbolizes life-giving energy, leadership, and royal authority.

🌕 Moon (WOL, 월)

The white moon is yin—the passive, feminine counterpart, tied to night and the queen. It offers balance, reflection, and emotional depth. Together, sun and moon create cosmic harmony.

🏔️ Five Peaks (OBONG, 오봉)

These five mountains aren’t random. Each peak corresponds to one of the Five Elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, water), the foundational energies that drive natural cycles of creation and destruction. They also echo Korea’s rugged terrain and spiritual reverence for mountains.

🌊 Waterfalls & Waves

Water is more than just scenery—it represents qi (기), the vital energy that animates all things. The flowing streams suggest movement, abundance, and renewal—a world in motion, never static.

🌲 Pine Trees

These evergreens stand for integrity and resilience. In Korean culture, pines endure all seasons without shedding leaves, making them a classic symbol of longevity and moral uprightness—qualities expected of both monarchs and ministers.

Even the colors carry deep significance. The royal screen’s palette is built on Obangsaek (오방색), Korea’s five-directional color system, where each hue maps onto a cardinal direction, a season, a life stage, and an element:

Blue/Green (Wood) — East, spring, birth

Red (Fire) — South, summer, growth

Yellow (Earth) — Center, late summer, fruition

White (Metal) — West, autumn, harvesting/sharing

Black (Water) — North, winter, rest

Put it all together, and Ilwol Obongdo isn’t just a backdrop—it’s a philosophy in paint. It’s a visual blueprint for how the universe operates, how a king should rule, and how harmony must be maintained between heaven, earth, and humanity.

In modern terms? Ilwol Obongdo is basically a visual workflow for how the world should run—2D art with 4D wisdom.

Humans in the Middle: Cheon • Ji • In

East Asian thinkers talk about Cheon-Ji-In (천지인)—Heaven, Earth, Humanity—as three interlocking gears. Heaven supplies principle, Earth supplies material, and humans mediate the two. Ilwol Obongdo is deliberately incomplete until a person—specifically the king—sits in front of it. The monarch becomes the “Human” gear that locks Heaven (sun & moon) to Earth (mountains & water). A Joseon throne room wasn’t décor; it was live-action cosmology.

Neo-Confucian Remix: When Three Teachings Collide

Joseon didn’t just bolt Taoist yin-yang onto Confucian ethics.

Neo-Confucianism was a tri-fusion super-app: Confucian duty, Taoist cosmology, and Buddhist mind-science merged into one operating system. The result? A king whose job description was “cosmic mediator + community caretaker,” not “divine dictator.”

From Tao to Taegukgi to Quantum Physics

Taoist origin story: from undifferentiated void (無) comes yin & yang, sparking the Five Elements.

Taegukgi, the Korean flag, visualizes that endless dance—opposites in perpetual embrace.

Visual breakdown of the Korean national flag, Taegeukgi, showing the yin-yang center (Taegeuk) and four trigrams (괘). symbolizing the elements. Source: Smarthistory – Korean national flag Physicist Niels Bohr loved the idea so much he put the yin-yang symbol on his coat of arms with the motto Contraria sunt complementa (“opposites are complementary”).

Just like the Taegukgi, Ilwol Obongdo is another visual icon that reinterprets shared East Asian philosophy through a uniquely Korean lens.

Dualism says good guys punch bad guys.

Ilwol Obongdo—and a lot of K-storytelling—argues the real game is integration, not knockout.

A Royal Prop You’ve Seen a Hundred Times (But Never Noticed)

📍 Gyeongbokgung, Deoksugung, Changdeokgung

Original royal screens

These historic palaces still display Ilwol Obongdo behind the royal throne, just as it was during the Joseon dynasty—reminding visitors that the king ruled as a cosmic mediator, not a divine monarch.

💸 ₩10,000 banknote

National shorthand for “legit authority”

Look closely at Korea’s 10,000 won bill—the reverse side features Ilwol Obongdo, cementing its status as a national symbol of righteous leadership.

🎬 Moon Embracing the Sun (해를 품은 달, 2012)

Drama = celestial romance, screen = stage for fated love

Even hit K-dramas have paid homage to Ilwol Obongdo. In Moon Embracing the Sun (해를 품은 달), the royal court is designed to evoke the cosmology of the sun, moon, and five peaks. The two romantic leads—symbolizing opposing cosmic energies—are visually framed just like the screen itself: the king (sun/yang) and the queen (moon/yin) bound together by fate, duty, and heaven’s design. It's not just drama—it's deliberate symbolism.

📺 The King's Affection (연모, 2021)

Drama = gender-swapped kingship, screen = mask of cosmic legitimacy

In this historical K-drama, a secret shakes the foundations of the palace: the crown prince is actually a woman in disguise. Park Eun-bin plays the first fictional female king of Joseon, navigating court politics, identity, and forbidden love.

Behind her throne? The Ilwol Obongdo screen—unmistakable and unchanging. Even in a story that defies gender norms, the backdrop signals legitimacy, cosmic order, and the weight of the crown. It’s more than just scenery—it’s the throne room’s silent witness and stamp of royal approval.

🏆 K-pop Demon Hunters award show

Idol = modern “king,” screen = cosmic stamp of approval

When a Joseon king took his seat, the painting came alive. So does HUNTR/X’s Rumi, center stage—activating the Ilwol Obongdo-inspired backdrop and transforming it into a living visual promise. The moment she takes her place, the ancient symbol becomes whole again.

But here’s what makes Rumi the perfect modern embodiment of this ancient philosophy: she’s neither purely good nor purely evil.

Like the yin-yang symbol itself, she contains both light and shadow, strength and vulnerability. This isn’t a flaw in the storytelling—it’s the entire point. Korean narratives, rooted in this monistic worldview, don’t traffic in absolute heroes or villains. Instead, they explore the complex humanity that exists in the space between extremes.

This is precisely why Korean content resonates so powerfully with global audiences. In an era exhausted by binary thinking, Korean stories offer something revolutionary: characters who embody the full spectrum of human experience.

Rumi completing the cosmic screen isn’t just visual poetry—it’s a philosophical statement about integration over division, complexity over simplicity.

In the animated series, the backdrop isn’t just pretty set design—it’s a bold homage to Ilwol Obongdo, reimagined for the K-Pop age.

Power, balance, and presence—all in one frame.

There are plenty more places where Ilwol Obongdo quietly shows up—but let’s stop here for now.

The Modern Message: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters Now

For roughly 2,000 years, global civilization celebrated dualistic, top-down, “electric” energy—us vs. them, superior vs. inferior. The 21st century is pivoting toward holistic, inclusive, “magnetic” energy—seeking integration over separation.

Ilwol Obongdo embodies that shift. Where Chinese emperors leaned on absolute power and Japanese emperors on sacred bloodline, Joseon kings had to earn legitimacy every single day—mediating heaven and earth through virtue and service. The painting was their omnipresent reminder:

Balance the opposites.

Mediate the extremes.

Keep the cosmic playlist on repeat.

Sound familiar? BTS’s Love Yourself trilogy, Marvel’s multiverse plots, even workplace buzzwords like “servant leadership” all hum to the same frequency: complement, don’t conquer.

Ilwol Obongdo’s journey—from royal halls to K-pop stages—tells us some truths outlive every trend. In an era hungry for balance and collaboration, a 600-year-old screen feels startlingly fresh.

Pretty wild, right? A prop you barely noticed in a demon-hunting anime just served up a masterclass in cosmic ethics. That’s the stealth power of K-culture: weaving ancient wisdom into modern spectacle so smoothly you dance first and ponder later.

A royal screen once reminded kings to rule with balance and virtue. But what if the true source of legitimacy wasn’t cosmic harmony—but the people themselves?

⏭️ Coming Up Next: The People Come First—Minbon Sasang and Korea’s Ancient Democratic Spirit

Next week, we’ll explore one of Korea’s most powerful yet lesser-known political philosophies: Minbon Sasang (민본사상), the idea that people are the root of governance.

In Joseon Korea, justice wasn’t just for the living. As the old saying goes, “Even a ghost can rest in peace if its grievance is heard.” That’s how seriously rulers were expected to listen to the people—even the dead.

We’ll trace how this people-first mindset shaped Korean institutions, from public grievance drums to royal self-critique rituals—and how its legacy echoes in Korea’s modern civic movements today.

Forget top-down rule. This was democracy from below, centuries ahead of its time.

Share this post