14 (4) The Korean Instinct to Save the Nation: From Cigarettes to Gold Rings

What Would You Give to Save Your Country? Here’s What Koreans Did

🎧 Bonus Audio: I’ve created a conversational audio version using NotebookLM, featuring extra insights and stories that didn’t make it into this post.

This is Part 4 of the series The People’s Mandate: Korea’s Democratic Edge, a special miniseries within Growing Up in Korea.

Let’s play a quick game.

Your country is about to collapse—either to a foreign power or to a financial meltdown. What do you do?

Quit smoking for three months?

Hand over your grandmother’s wedding ring?

Melt your Olympic medal?

If you're Korean, the answer tends to be:

“Of course. And we’ll do it together.”

Welcome to Korea’s unique brand of patriotism—a collective instinct so strong, it has pulled the nation back from the brink more than once.

Today, we’ll look at two of the boldest episodes in Korea’s modern history:

the 1907 National Debt Repayment Movement

the 1997 Gold-Collecting Campaign during the Asian Financial Crisis

These weren’t government campaigns.

They weren’t tax drives or war bonds.

They were nationwide volunteer movements—powered by civic duty, community spirit, and some pretty creative sacrifices.

Act I: Cigarettes, Jewelry, and Korea’s Civic Awakening

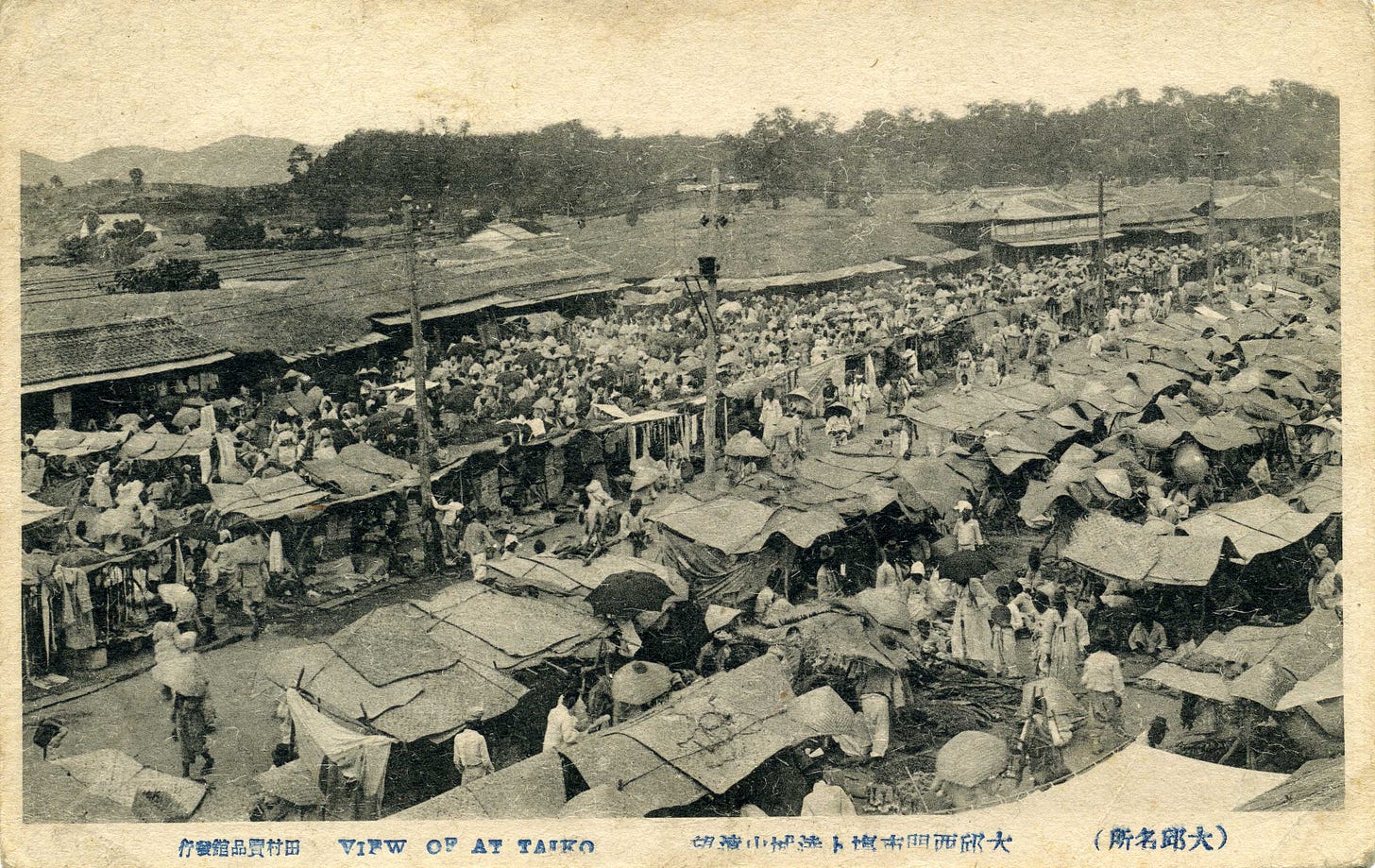

Picture Korea in 1907:

Not yet a Japanese colony, but increasingly under Japan’s thumb.

Japan, positioning itself as a benevolent modernizer, forced Korea to accept huge loans—allegedly for railways and reform, but in reality, to make the country economically dependent.

By 1907, Korea owed 13 million won—about the entire national budget for the year.

And everyone knew what was coming next: full-blown annexation.

So, what did people do?

They didn’t wait for the king to fix it.

They didn’t write angry letters.

Instead, a group of civic leaders in Daegu (a city in southeastern Korea, known today for spicy food and political conservatism) had a radical idea:

👉 “What if every Korean quit smoking for three months and donated the money saved to pay off the national debt?”

It sounds like a thought experiment—but it wasn’t. It actually happened.

Newspapers spread the idea, and the country caught fire with purpose.

Everyone joined in:

students

scholars

street vendors

even gisaeng (traditional female entertainers, often dismissed but here, stepping up).

Even Emperor Gojong joined the cause.

But it was Korean women who led the charge.

They formed Jewelry Abolition Societies (패물폐지부인회) and donated their wedding rings, hairpins, and heirloom accessories.

Children gave up their allowance.

Thieves and beggars contributed, too. One even said:

“Though my job is humble, my duty to the nation is the same as anyone’s.”

It was a rare grassroots movement to save the country—uniting people across class, gender, and region.

And it wasn’t just about money. It was about sending a message:

Korea is a nation worth saving.

Did it work?

Not financially. Japan cracked down. Leaders were jailed. Most funds were seized.

But in spirit?

It was a revolution.

The idea that ordinary people—not royals or generals—could rally to protect the nation?

That idea stuck.

Act II: Gold Rings, Olympic Medals, and a Nation on the Brink

Fast forward to 1997.

Korea has gone from a colonized nation to an industrial powerhouse.

Then—boom. The Asian Financial Crisis hits.

Stocks crash. Banks collapse. The government turns to the IMF for a bailout.

For many Koreans, this felt like national humiliation.

Then came the call:

“Let’s gather our gold for our nation!” (애국 가락지 모으기 운동)

It started with a civic group—the Saemaul Women’s Association (새마을 부녀회)—and soon became a full-blown, government-supported movement.

By early 1998, major broadcasters like KBS were running wall-to-wall coverage, turning the campaign into a national event.

But this wasn’t just another donation drive.

People brought in their gold—baby rings, wedding bands, family heirlooms, even Olympic medals.

The gold was melted and sold for dollars.

Donors received Korean won in return, based on market prices.

It was less “charity” and more patriotic currency exchange—gold traded for won to boost national reserves.

The response? Overwhelming.

Newlyweds gave up their rings.

Parents handed over their baby’s dol-banji (a ring given on a child’s first birthday).

Elders parted with gifts from their adult children.

Even Cardinal Stephen Kim Sou-hwan, Korea’s first Catholic cardinal, donated the gold cross he received at his appointment. His words echoed across the nation:

“Jesus gave his body. This is nothing.”

In total?

3.5 million people participated—roughly one in four Korean households.

They donated between 225 and 227 tons of gold—worth over $2.1 billion (in 1998 USD).

Was it enough to pay off all the debt?

No. It covered only about 10% of the IMF loan.

But the message?

Loud and clear:

Koreans would not let their country fail.

The IMF took note—and eventually eased Korea’s repayment terms.

Korea repaid its loan three years early, in August 2001.

The Other Side of the Coin

Of course, not everything was golden.

Critics pointed out that ordinary citizens bore the burden, while corporations—the very ones who caused the crisis—got off easy.

Some companies even manipulated the system to their advantage.

And many people later regretted donating gold just before prices skyrocketed.

Still, the Gold-Collecting Campaign remains a shining example of civic unity.

It wasn’t about economics alone—it was about identity.

Why Do Koreans Do This?

What makes Koreans so willing to sacrifice for the nation?

Part of it is historical:

Centuries of invasions, colonial rule, and national trauma have hardwired the belief that when the nation is in crisis, everyone is at risk.

But there’s more.

These weren’t state mandates.

They were grassroots explosions of civic energy.

People wanted to act.

Not because the government asked—but because their neighbors were already doing it.

And weirdly? There’s joy in it.

A kind of collective pride—like cheering for the same team, but with gold rings instead of foam fingers.

Living Legacy: More Than Just a History Lesson

These aren’t just stories from the past.

They’re referenced every time Korea faces a crisis.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the same spirit emerged:

donated masks

fundraisers

meals for frontline workers

It’s become part of Korea’s DNA:

In crisis, come together.

Other countries have studied these movements, asking:

“How can we inspire that kind of collective action?”

Final Thoughts: The Power of “Us”

So what is Korea’s real secret?

It’s not just about patriotism.

It’s about this reflexive belief that:

“When things fall apart, we don’t ask what the government will do. We ask what we can do—together.”

So next time you see a Korean heirloom—a ring, a medal, even a cigarette pack—remember:

It might be more than just a personal item.

It might be a reminder of a nation that survives—again and again—through the power of us.

But that raises a deeper question:

Where did this “power of us” come from?

Why are Koreans so quick to rally, to sacrifice, to act not as individuals, but as one?

It wasn’t born overnight.

It was shaped—by history, by loss, by the land’s rugged mountains and tightly clustered villages, by a system where even the grievances of ghosts could be heard, and by moments of collective resistance and hope.

There’s a long story behind this instinct.

It’s one we’ve only just begun to unearth.

And in the coming weeks, I’ll try to unravel it—one chapter at a time.

Stay with me. The next story begins in 1919.

👀 Coming up next:

We’ll dive into how the March 1st Movement (3.1 운동) in 1919 helped shape Korea’s modern idea of “nationhood” and laid the foundation for its democratic spirit.

always cool to read you about korea and learn moore from an another prospective (from italy!!)