16(6). The People Own This Land: A Revolution That Never Ended

Uncover how communal land ownership and a peasant uprising forged Korea’s unique path to democracy—from bamboo spears to candlelight protests.

🎧 Bonus Audio: I’ve created a conversational audio version using NotebookLM, featuring extra insights and stories that didn’t make it into this post.

This is Part 6 of the series The People’s Mandate: Korea’s Democratic Edge, a special miniseries within Growing Up in Korea.

Let’s start with a simple question: Who owns Korea?

Your instinctive answer is probably, “The people, of course.”

And you’d be right. Anyone with a shred of common sense would say the same.

But in Korea, the phrase “the people are the owners of this land” isn’t just something you find in dusty civics textbooks. It’s not an empty slogan trotted out during campaign season. And it’s definitely not just a feel-good phrase printed on protest banners.

It’s the bedrock of modern Korean democracy—and more than that, it’s a lived truth that stretches back thousands of years.

Buckle up. We’re about to time-travel from Neolithic rice paddies to the neon-lit streets of Seoul, connecting bamboo spears to smartphone flashlights.

The Ancient Seed: How Owning the Land Became a Moral Right

To understand this belief, we have to go way, way back—like 5,000 years back.

In ancient Korea, land wasn’t just property. It was sacred, communal space.

Archaeological evidence from the Neolithic settlement of Munam-ri (문암리) in Gangwon Province shows signs of early agricultural life organized around shared land use.

Farming wasn’t just labor—it was livelihood, ancestry, and spiritual obligation.

By the Joseon Dynasty (Korea’s last dynastic kingdom before it became the Korean Empire in 1897), Confucian hierarchy may have shaped much of society, but the idea that “those who farm should own the land” (경자유전) had taken root as an ethical norm—even if it wasn’t always legally enforced.

For generations, Korean peasants believed they were the rightful stewards of the land they cultivated.

They dug irrigation canals together. They harvested as one. And they buried their ancestors in the same soil that sustained them. Losing that land wasn’t just an economic blow—it meant losing memory, lineage, and identity.

When the Rulers Failed, the People Rose

By the 19th century, corruption and foreign pressure had brought the Joseon state to its knees. Instead of protecting the nation, government elites invited intervention from China and Japan.

That’s when something extraordinary happened.

In 1894, Korean peasants—organized under a grassroots religious movement called Donghak (Eastern Learning)—took up bamboo spears and farming tools and declared a rebellion. Their slogans?

"Protect the nation, comfort the people" (보국안민)

"Expel the Japanese and the Westerners" (척왜척양).

Let’s pause here.

They didn’t say, “Restore the king.”

They didn’t say, “Obey the bureaucrats.”

They said, in essence: If you won’t protect this land, we will.

This wasn’t just a protest. It was a revolutionary claim: that the people—not the monarch, not the court—were the rightful guardians of the nation.

The Slaughter at Ugeumchi—and the Spirit That Survived

The uprising was met with brutal force.

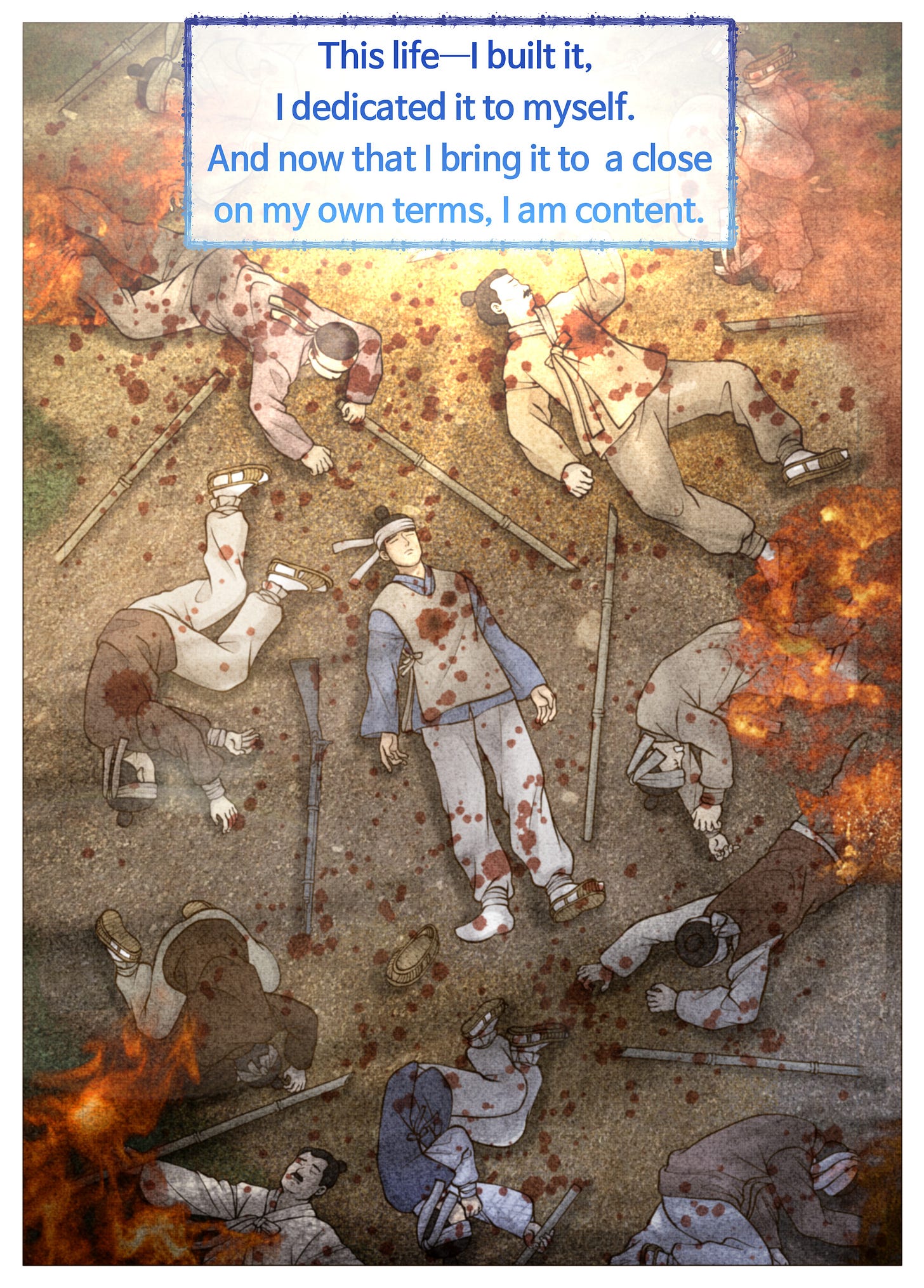

At the Battle of Ugeumchi, some 20,000 peasant fighters—armed mostly with bamboo spears—charged Japanese troops equipped with Gatling guns. Only 500 survived. In the weeks that followed, an estimated 300,000 more were massacred across the country.

And yet—Donghak didn’t die.

In an almost mythic twist, the movement transformed. Under the leadership of Son Byeong-hui, Donghak evolved into Cheondogyo (“Religion of the Heavenly Way”), growing to over 3 million followers by the early 20th century. It carried with it a redefined theology:

In-nae-cheon (人乃天) — “Man is Heaven.”

If every person is heaven itself, how can any ruler stand above the people?

From Sacred Belief to Political Action: The March 1st Movement

By now, if you’ve read my earlier post on the March 1st Movement, you already know how pivotal it was.

But for those just joining: on March 1, 1919, leaders of Cheondogyo—the spiritual successor to the Donghak movement—joined forces with Buddhists and Christians to declare Korea’s independence from Japan.

Fifteen of the 33 national representatives who signed the Korean Declaration of Independence were Cheondogyo members. Their grassroots network—built on religious conviction and community trust—enabled the movement to spread nationwide in a matter of days.

The declaration began:

“We herewith proclaim the independence of Korea and the liberty of the Korean people as the rightful nation.”

This wasn’t just an anti-colonial statement.

It was Donghak’s core message reborn in modern political language:

The people are sovereign.

We own this land.

And no empire can take that away.

Article 1: Democracy as Sacred Inheritance

When South Korea finally became a sovereign state in 1948, the very first article of its constitution made no compromises:

1) The Republic of Korea shall be a democratic republic.

2) Sovereignty resides in the people, and all authority comes from the people.

This clause wasn’t borrowed from Western democracies.

It was deeply indigenous to Korean political memory.

It echoes Ugeumchi. It echoes March 1.

And it echoes the bamboo spears that once faced down imperial bullets.

Resistance by Default: Why Koreans Don’t Sit Quiet

Even after independence, democracy in Korea was never guaranteed. Military dictatorships ruled for decades. But every time authoritarianism returned, so did the people.

In 1960, 1980, 1987, 2016–2017—and most recently, in 2024–2025—ordinary citizens once again flooded the streets to say the same thing:

This country is ours.

(We’ll explore Korea’s major democratization movements in future posts.)

And it wasn’t just about abstract ideals.

Many saw their power, their land, and their dignity being stolen by the elites—whether it was corrupt politicians, chaebol conglomerates (family-run corporate giants like Samsung, LG, or Hyundai that dominate the South Korean economy), or real estate speculators chasing profit over people.

The candlelight protests of 2017 and the light-stick protests of 2024 that brought down presidents weren’t sudden flames.

They were torches that had been lit centuries ago.

So What Does It Mean to Say “The People Own This Land”?

It means that democracy in Korea isn’t just a system.

It’s a memory.

It’s a story told through blood, belief, and bamboo.

It means that to be Korean is to inherit a covenant—not just with your ancestors, but with the soil itself.

And when the powerful forget, the people remind them.

Coming up next:

The Japanese colonial era isn’t just a chapter in Korea’s past—it’s a living memory. Koreans revisit that time again and again: in textbooks, films, TV dramas, novels, and family stories.

The pain of that era—and the fierce determination of those who rose up against it—are never far from the cultural conversation. These stories are remembered, retold, and passed down.

In the next post, we’ll take a breather from history-heavy analysis and explore how Koreans have turned this painful legacy into powerful storytelling.

K-Drama is having a global moment, after all.

And let’s be honest: no one does emotional storytelling quite like Koreans.

So get ready for resistance, resilience, and maybe a few tears—told the K-way.

This is fascinating and inspiring. I was in S. Korea most of 2000 but could not spend much time away from work. The land is spectacular. Most of the people I met were patient with my ignorance.

The March 1st Movement was both a heroic undertaking and a tragedy. The school girls' photos in Seodaemun Prison are heartbreaking...that they were so brave and almost children. The Donghak revolution was an example of the strength inside the Korean heart when an injustice is perpetrated. These are the people who impeded the martial law almost-coup of President Yoon. I am so proud of them! What a great article and reminder of the greatness of the Korean people.